Overview of the Modern Knife Maker

Modern Knife Making by Individuals

This page offers an overview of the modern singular knife maker. This page does not discuss

factories, boutique shops, or other ventures where groups of people, corporations, or businesses

employing more than one individual manufacture knives. This is about the individual modern knife

maker and the terms, type of work, techniques, scope of business, and direction of art that modern knife making

offers for the individual craftsman and artist.

The modern knife maker makes knives, of course. There is,

unfortunately, no fashionable or more elegant term

for the person who makes knives. When the term knifemaker is used in contemporary

times, it usually refers to an

individual, working in a shop or studio, creating knives, daggers,

swords, or other edged tools and weapons from raw materials. The

term knifemaker is a neologism, a new word that means so much more than

the word knife and maker do separately. There are many

types of knifemaker (sometimes casually referred to as the maker), and the maker's level of involvement

varies. The first distinction is that level of involvement.

- Hobbyist: People often start out

making knives as a hobby. They may purchase kits to finish and

assemble, may be given old knives to repair or refurbish, or may

make knives from found materials like steel scrap or wood cutoffs.

They may work with a minimum amount of tools, sometimes in a small

shop or garage (hence the term garage-maker) and enjoy the interest of knife making.

This is how I started making knives in 1978-9: as a hobby. My first

knives were given away.

- Part-time knife maker: Part-time makers are

usually more serious than hobbyist makers, and are actively selling

what they make. Knife making is not their main vocation though, and

they derive income from another source, job, or retirement, which

often is essential to furthering their part-time knife making.

Incidentally, these are most of the knifemakers you may encounter on

the Internet, at shows and exhibitions, and in publications. They

may work in a small or large shop with minimal equipment or large

investments of complex machinery, depending on the type of knife

they make and sell. They may spend only a moderate amount of

time making knives, or may be deeply involved investing huge amounts

of time, up to as much time as a full time job. I was a

part-time knifemaker for about 8 years, before I went full time.

- Professional Knife Maker: Also called

full time knifemakers, this defines knife makers that have chosen

the field of knife making as their job or vocation. Their level of

involvement is extremely high, and as professionals they derive their main income from

making and selling knives. They must have a well-equipped,

professional shop or studio, often have an active and viable

business store front in their community, and vigorously participate in the

business of making and selling knives year after year. Their

involvement can be so high and expansive that they also

professionally consult for other businesses, organizations,

military, and professionals. This is

what I am now, and have been since 1988. I take my profession seriously, and it is how I derive all of my

income for my family and myself. This is my regular job, and I love

it!

- Career Knifemaker:

This is a professional knifemaker who has made an entire career of

making knives. I had to include this term to celebrate 2018, which

is my 30th year of being a full time professional custom knifemaker.

This is my career, and I'm honored that I've been given the chance

to serve others for so long. Just because I've had a full career of

knifemaking, it doesn't mean it's over. In fact, some of the very

best work I'll ever do is being done right now, in 2018, and next

year, and the years after that!

I have been a professional full time knifemaker since 1988.

Back to topics

There are several specific distinctions that describe how the modern

knife is made that are important: handmade or custom, and other terms

that are more general.

- A handmade knife is generally

described as a knife that is made offhand. What this means in detail

is that human hands must be in control of all the functions of knife

making, like holding the hammer that forges the knife, holding the

blade against the grinder, guiding the drilling, milling, and

shaping by direct control of the hand. What this term excludes is

any activity that is automated, where the blade or component is

clamped in a fixture and an automated machine, such as a computer

numerically controlled milling machine (CNC mill) automatically

cuts, shapes, and forms the component. The advantage to handmade

knives is that subtle nuances of control in the machining and

finishing can occur, leading to a much more desirable and often

better made product. There is a reason you don't see finely finished

knives coming out of a computer automated device. I go into that in

greater detail in my upcoming book.

- A custom knife by exact definition is

a knife made to a customer's order. These are knives that are

commissioned by clients with specific features and details and

are created by the knife maker for that client. While a knife may be

handmade and custom, a knife that is not specifically ordered for a

specific client may be handmade, but is not custom. There is a lot

of lax usage of the word custom on the Internet, in discussions,

and in publications. There are even major knife shows that have

the word custom in their name, yet the participants in the

show do not sell custom knives, but knives made and created to sell

to the public at large, in essence, inventory knives. The only way

these shows could be called custom is if the knives at the show are

ordered by and made individually unique for each client coming to

the show. Why would these interests hijack the word? I believe this is because the word custom

denotes a higher level of participative quality. If a knife maker

makes custom knives, that means he is capable of a wide variety of

process and a high level of skill, in that clients seek him out and

offer direct commissions, whereas a non-custom maker simply makes

and sells knives made by his own design. Read more about the

custom knife description on my

Custom Knives Page

- Other terms are varied and non-specific like bench made

which is a term that once was used to denote a knife

that is made on a tool bench and not by automated process, though

that can be vague description. Are knives made on a tool bench

simply assembled from components manufactured overseas? Because

the term is associated with a knife factory, the term

has fallen out of favor and has lost meaning in the modern knife

world, and is best avoided altogether. Other terms prevalent in this

industry are boutique shop, custom shop,

production facility. What do you call a knife made

in a small factory or by a group of people in a boutique shop, small

factory, or manufacturer? Why a factory knife or manufactured knife,

of course, because that is what it is.

It is not custom, not handmade, and not unique or original but a

mass produced and manufactured product. The reason for these

curious names for knife manufacturers is one of advertising only.

More information about this topic on my Business of Knifemaking

at this bookmark.

Please remember that there is no right or wrong way

to make a knife, only different methods. The source of

the knife should clearly and easily define how the

knives are made, where the components come from, and who

supplies them as well as the processes used and their

origin, and the alloys and components of construction

that are recognized by official entities like the AISI

(American Iron and Steel Institute), ASME (American Society of

Mechanical Engineers), and SAE (Society for

Automotive Engineers).

Back to topics

It's interesting to see the confusion about the simple word handmade,

and this has gone on for decades in our profession. People who buy fine

knives obviously prefer handmade knives, since there really is no finely

made and highly priced collector's grade factory or machine-made knife.

There are no extremely finely made combat knives made by machine either,

and that escapes most people who do not realize that there is a large

demand for an extremely high quality tool and defensive weapon that is

necessary in combat, counterterrorism, search and rescue, and emergency

situations. It's

common knowledge that the minute a particular operation is handed over

to a machine, and taken from the control of the human hand, the product is less

desirable and less valuable overall.

The reason for this is simple: a

machine has very specific operations, and very specific and controlled

functions, and has no ability to create, grow, advance, learn, and

improve the product it creates. It simply repeats a function, over and

over, usually at great speed. Because of this automation,

machine-produced products are cheap. Creating cheap products means that

they must be sold in great volumes, and since most of the world does not

have significant money to spend on knives, the masses only buy cheap

knives. Machine-made and machine-produced products are and will always

flow in a downward fashion, when concerned with quality, price, and

options.

Machines are created by man for many reasons, but let's just look at

one: drudgery. When I think of the word drudgery, I think of a flock of

sweaty, laboring women crouching at the edge of a stream, pounding

clothes on rocks to wash them. The clothes are filthy because they

belong to their men, who are sweaty and laboring in the fields, guiding

a plow, bent over, pulling weeds, prying big rocks out of the earth so

the crops to come will flourish. This was the plight of my ancestors

here in this country, dating back to the Revolutionary War times. Most

of my ancestors, when researched far back enough, were farmers,

laboring, sweating, working, and suffering to stay alive. Most people

can claim this.

This is the main reason machines were created, to make easier and

faster the labor, particularly repetitive, monotonous, difficult labor

like washing clothes and tilling soil. In knifemaking, one of the most

laborious, wearisome, and repetitive operations is cutting

out steel, or blanking. The reason is because even in the annealed and

softened state, cutting must commence slowly, with some force and plenty

of control, particularly in the higher alloy steel types. Since metal

cutting bandsaws mostly cut straight lines, this is a particularly

frustrating experience to produce highly curved forms. Do you then

wonder why most knives are fairly straight pieces of flat metal bars?

What about the bolsters, those little, thick, tenacious blocks of metal

everyone wants to eliminate, simply because they are so difficult to

produce? More about

Bolsters here.

For knifemakers, sawing or blanking blades can become a wearisome

issue. I've seen makers do just about anything to not have to saw out a

blade, including employing plasma cutters, grind-profiling, water

jetting, and even convincing their wives to push metal through their

bandsaws (I'm not kidding)! Rather than approach the problem head-on,

they want to make it easier, and that's understandable. They want to get to

the fun stuff, the part of knifemaking that makes a bar of steel look

like a knife, the grind, and the handle (mostly the handle, since wood,

horn, bone, and plastic is far easier to work than metal). In the last

decade, with the advancement and availability of the computer aided

design (CAD) programs and computer aided machining (CAM) operations,

would-be knifemakers can simply sit on their fluff at a computer monitor

and mouse, click up a design (and call it "work") and then email their

creation to a company that will cut out their blades with a water jet,

and sent them the blanks. I see this more and more in our trade,

and it's easy to see why; it's simply easier. But as in

this section on my "Heat Treating and Cryogenic Processing of Knife

Blade Steel" page, easier and cheaper is not a good road to embark on,

if the journey is to lead to a successful artistic and desirable knife

profession.

When they have knives cut out with a water jet, they may be surprised

to learn that they and their knives are not welcome at knife shows, and

they can be looked down upon by other makers. There are a few distinct

points to this.

- The first is the word "custom" and it's misuse

to describe a handmade knife show. This has been going on

for decades, and it's not likely to stop, but there are no "custom"

knife shows, even though they claim to be. Custom means

made to order, and the knives at most of these shows are

handmade. Usually, the word handmade conjures up images of folk

craft: quilts, barn decor, furniture made from rough branches, and

blue bottle trees. Seriously, put the term "blue bottle tree" into a

search engine and look at the images; what an incredible fascination

with this form and color! In any case, the word handmade is

less desirable than the word custom in the public show

venues, so custom is

the standard misuse at these events. More about that on my Custom Knives page.

- Handmade knives only. This has been

ongoing for decades, and the concept is this: as more

knife shows appeared in the 1980s, knifemakers in organizations (the

Knifemakers Guild, the American Bladesmith Society, the Professional

Knifemaker's Association) were confronted with more makers who were

surrendering their operations (the creation of their knives) to

machines. There were some pretty big-name makers doing this, and

they would have bits, pieces, and components even farmed out to

outside contractors while they did the assembly of the knives. These

knives they then called "handmade" in order to qualify for shows. I

know we had quite a huge split in the Knifemakers Guild about this

classification and qualification at that time, as these essentially

machine-made products were being called "handmade," in direct

conflict with show rules and the direction of the organization. I'll

go into this more in my book, but the members then demanded that at

the very least, documents (certificates of origin) were required so

that the method of knifemaking employed was disclosed to potential

buyers of the knives presented at these shows. Even today, some

shows require that operations of knifemaking be disclosed. Some of

the shows prohibit knives for sale that are even partially made by

machine control, and that includes water-jetting blades.

- Machines and machine control: Some people get

confused by this. Machines are used to make knives, nearly every

knife you see has, at one time, been touched by a machine. Even guys

who hand-forge are using machines: electric fan-driven forges,

machine welders, power trip hammers, hydraulic presses, and

grinding/sanding/finishing of at least one component of the knife

ensemble. So, with very few exceptions, we are all using machines.

The distinction is with machine control. When control of the machine: positioning,

movement, indexing, motion, action, or any operation of the machine

is controlled by a computer, it is no longer considered handmade.

Holding a blade by hand against a grinder qualifies as handmade,

because all of the grinding is directly controlled by human hands. Having a blade clamped to a tooling plate while a

computer-controlled CNC (computer numerical control) machine moves a

cutter against the blade is not handmade, even though a hand guided

a computer mouse in clicking out the design. Neither handmade is a

blade blank that is clamped against a table while a computer moves a

water jet (high pressure water cutting device) around the periphery

to create a blade blank. It's pretty easy to understand. If

any part of the making of the knife is under the control of a computer or

automated system, it's not entirely handmade.

When new makers are confronted with this, they are often upset. After

all, the rest of the knife is handmade; why is it important how the

blade is cut out? After all, it's only one operation, one step.

This illustrates the slippery slope of knife making method and

disclosure. People want handmade items, hand crafted, hand-created, made

one at a time by hand. This is where the higher value lies. Some new,

inexperienced, or less aggressive makers

want a shortcut. They want to go to a handmade knife show, but sell

items that are not entirely handmade. The problem is that there is no

stopping on this slope, and pretty soon, other machine operations are

ignored, like grinding, tumble finishing, and component milling, and where exactly will

this stop? Does a knife made 50% by machine under the control of a

computer still qualify as handmade? 70%? 90%? This is the problem.

A knife that is handmade means a knife that the most critical steps

are under

direct control of the human hand. There will always be machines that we

use to create or works, chemical processes to do the work for us, heat

(and cold) automation in our process control. Some completely monotonous

tasks (like surface grinding a bar of steel) are automated on purpose;

they eliminate drudgery and aren't critically necessary to the final

blade shape or geometry. This is why operations like surface grinding

are sometimes performed at the steel supplier, even before he ships the

steel. In heating and cooling, there is no hand on a big switch turning

the oven or cryogenic refrigeration system on and off; we use automated

controllers to do this. In our trade, handmade means designed,

cut, blanked, milled, ground, heat treated, finish ground, fitted,

handled, and (hopefully) sheathed using direct control of the maker's

hand. Above all, the process should be clearly disclosed by the maker

when asked by a client who will purchase the maker's work.

There is nothing wrong with automated blanking, but it should

absolutely be disclosed to any interested client or buyer; it's their

money. And the

operators of knife show venues have the right to include or reject any

knifemaker's works based on their classifications of how the knives are

made. It is, after all, their show.

Back to topics

More

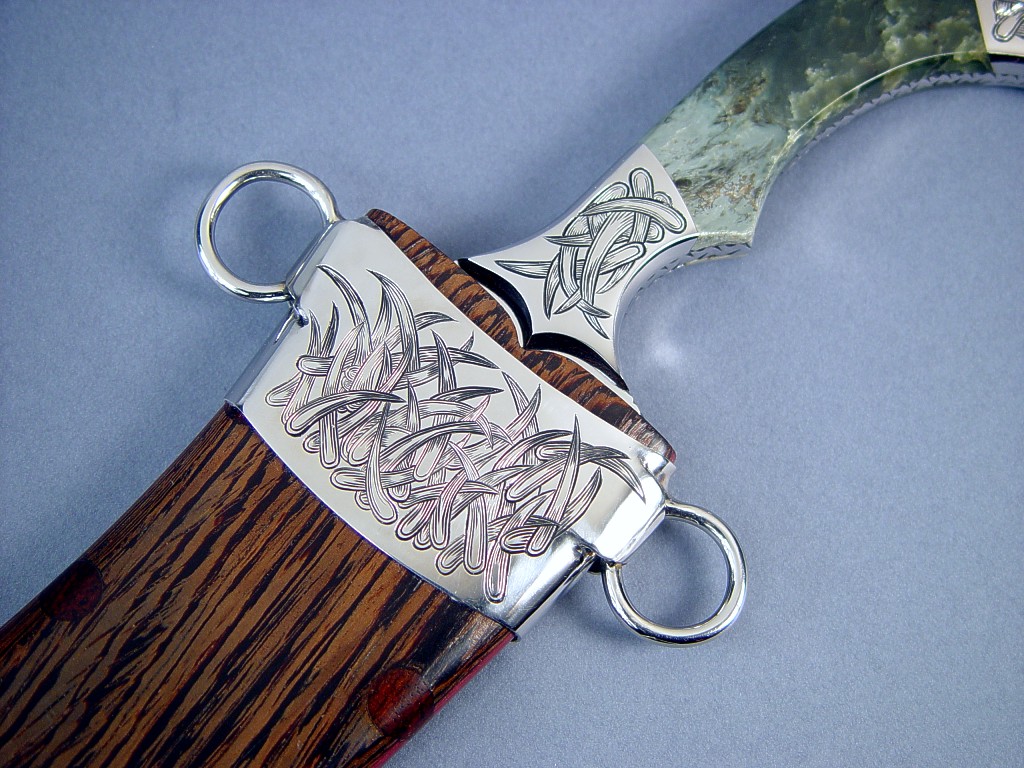

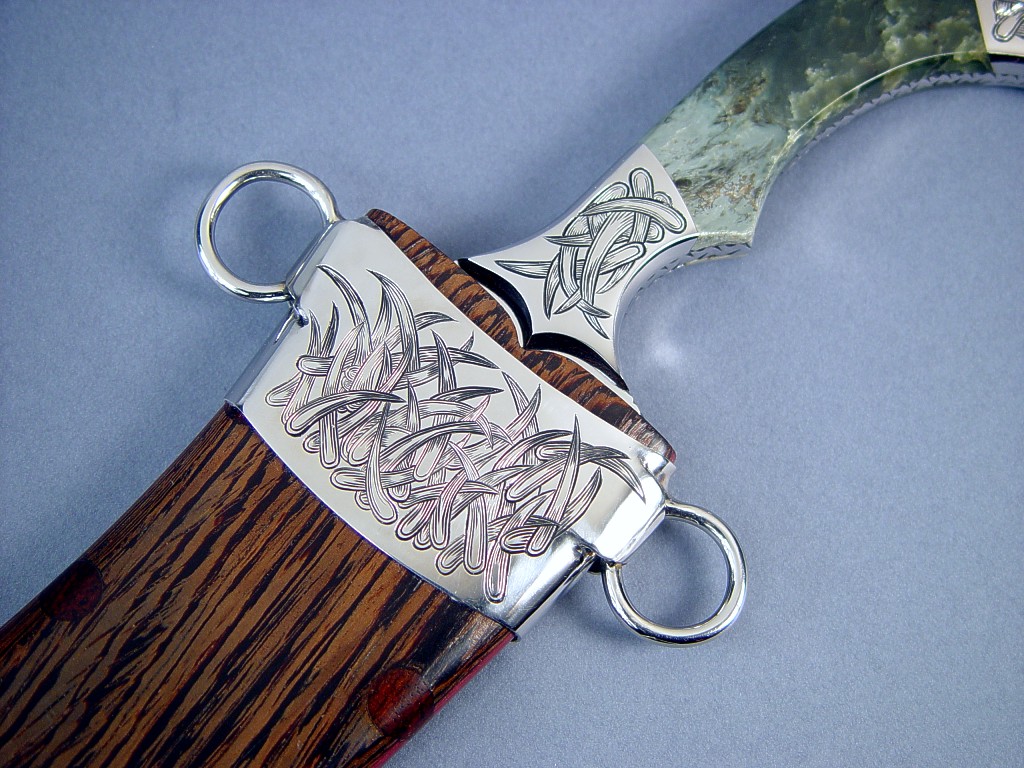

More about this "Korath"

Counterterrorism Knife

You might be surprised at who

purchases custom and handmade knives. Just like any other modern

interest, there are varying levels of involvement and interest in

the modern knife client.

- Knife enthusiasts are simply people who are interested in knives. That includes a

tremendous cross section of humanity as every human, sooner or

later, will use a knife. Knives elicit a visceral response from

nearly every human; in every culture they are recognized for what

they are and what they can do. You could not say that about a

fork, a car key, a trivet, or an MP3 player. Knives are universally

known and accepted. This doesn't mean that they are accepted with positive

reactions, and I talk about those trends in my book. What it means

is that the level of interest in owning fine knives is widespread,

and spans cultures, time, and nations. People may become enthusiasts

if they simply own one good knife, but most have more than one.

Anyone who is reading this with interest is probably a knife

enthusiast.

- Professional knife users are people

who must use a knife in their trade or occupation.

This could mean a packer on the line in a slaughtering plant, but

that type of knife is cheap and you won't find any fine custom

knives at a butcher shop (unless he's a very accomplished butcher).

You will, however, find fine and sometimes custom handmade knives in

the hands of a fine chef. You will see well-made knives in the hands

of professional hunting guides and outdoorsmen. You may find

professional knives in the hands of police, SWAT teams, Emergency

Response teams, firefighters, first responders, and Paramedics. Most

significantly for guys like me who make

combat knives, you'll find

handmade and custom knives in the hands of military professionals,

infantrymen, federal officers, police, and combat soldiers.

Professionally made knives are used by combat search and rescue

(USAF Pararescue), survival specialists (SERE), Special Forces,

Navy SEAL Team members, Special Operations, Marines, and Explosives Ordinance Disposal

technicians. These are knives designed with the input of and

used by the some of the top counterterrorism teams in the world. Knives used in these fields must excel in performance,

construction, wear characteristics, and accessibility as lives

can depend on their performance. One of my greatest honors is

making counterterrorism knives for some of the top counterterrorism units in the

world, lives that can literally mean life and death in their wear,

design, construction, and use.

- Collectors are a special

group of people who collect knives because of their interest, the

value, and long term investment potential of the knife. Well-made

knives by world-class knife makers appreciate in value over time,

and most other knives do not. It is not just the increase in

monetary value of the knives that make them suitable for collection;

collectors collect knives because they love them. You can see why on

the many testimonials on this site. The type of knife, the style of

a particular maker, a personal interest, or an appreciation of fine

knife design and craftsmanship are all building blocks for a knife

collector's interest. His interest may be in only a single example

from many different makers, a particular style of knife, or a

long term association with an individual artist who makes the kind

of knife that he likes. As his interest grows and the maker matures,

quite a collection can be amassed and the maker may develop a

substantial following among specific collectors.

Through the interest, support, and patronage

of knife enthusiasts, knife using professionals, and knife

collectors, a maker can continue to produce and grow over the years,

improving his knives, his skills, and his business.

Back to topics

When I started making knives, one could buy the best factory knife made for under $100.00. So most

knife makers started their work at $100 and the prices went up from

there. Now, there are some factory knives that are priced at several

times that. The reasons that custom and handmade knives are more

valuable than factory knives is usually clear when the knives are

put side by side and compared. For an in depth discussion of the

distinctions between factory and handmade knives, I've created a substantial page.

- Materials: though you may read many claims about

the superiority of particular knife materials on the

Internet and in publications, the materials are not the foundation

of the cost and value of a fine handmade knife when compared to a

factory knife or a poorly made knife. The reasons companies and individuals tout their

product materials as superior to others is typically merely an

advertising ploy. Though cheap foreign imported knives are often

made of inferior steels, other metals, and handle materials, many

factories and boutique shops use good steels in their blades and

durable handle materials, yet their knives do not rate of higher

value or investment grade due to many other important factors.

Today, our civilization creates and has access to the finest steels

and materials that have ever existed, and because of information

technology, knowledge about the proper application and use of these

materials is easily obtainable. Though some materials used may be

rare and expensive and may add to the base price of a handmade

knife, they, alone, are not the determinant factor in knife value.

What are these factors? Read about these distinctions on a

special page here.

- Patterns:

Countless patterns of knives, daggers, and swords have existed throughout mankind's

history. Any search of textbooks, historical sources, or on the

Internet will yield many thousands of patterns. At first, a new

pattern may seem novel and unique, but this is rarely the case.

It is not simply the knife pattern that

differentiates value in knives, though it can play an important

role. Read more about patterns, designs, and copyright issues on

my Business of Knife making page

at this bookmark.

-

Fit, Finish, Design, Balance, Accessories, and Service

are the six defining points that usually separate fine handmade

knives in value from mass produced, factory, or poorly made knives.

I go into these points in great detail on a

special page.

Back to topics

A great deal of knifemaking is understanding the relationship,

manipulation, combination, working, and finishing of a great variety of

materials. You could say that knifemaking is perhaps the most wide

ranging materials craft known. If you don't believe this, lets do some

simple comparison:

- A jeweler works in precious metals, and so does the knifemaker.

But the jeweler does not work in wear resistant, high strength tool

alloys, and no jewelry is meant to be a working tool. Rarely do

jewelers work in woods, even less so leather, and jewelry is

relatively small in size and not really expected to perform (apart

from buckles). While a jeweler may work with stone, rarely does he

work with any stone large enough for a knife handle, case, box,

sculptural stand component, or base.

- A carpenter or cabinetmaker works with hardwoods and joinery,

shaping and finishing, and may rarely work in supportive metal

structures. But he does not typically work in tool steels,

super exotic woods that can only be acquired by the inch, and

he doesn't work with any leather, plastics, or manmade materials.

- A shoemaker works with leathers, but does not work with hardened

high alloy metals, engraving, or metals machining.

- A machinist works with tool steels, but does not work with

leathers, woods, or embellishment.

II could go on and on, examining and comparing the materials sets of

various art and craft processes, and it's easy to see that a painter,

ceramics artist, photographer, woodcarver, clothing designer, sculptor,

and graphics artist all have a bit of the knifemaker's trade in them,

but the knifemaker, the truly dedicated knifemaker, has some of all of

their skills in his toolkit. To give you an idea of how this all works,

consider this:

- Programming, IT, Computer Technology: as a

knifemaker, I start with a functional coded, website, and actively

use computer technology for conversation, research, illustration,

and completion of all of the aspects of the public part of my

business. What you are reading right now is coded, by hand, in XHTML

markup language by hand. While I've removed the more complicated

parts of the coding, PHP and MySQL, computer science plays a big

role in what I do.

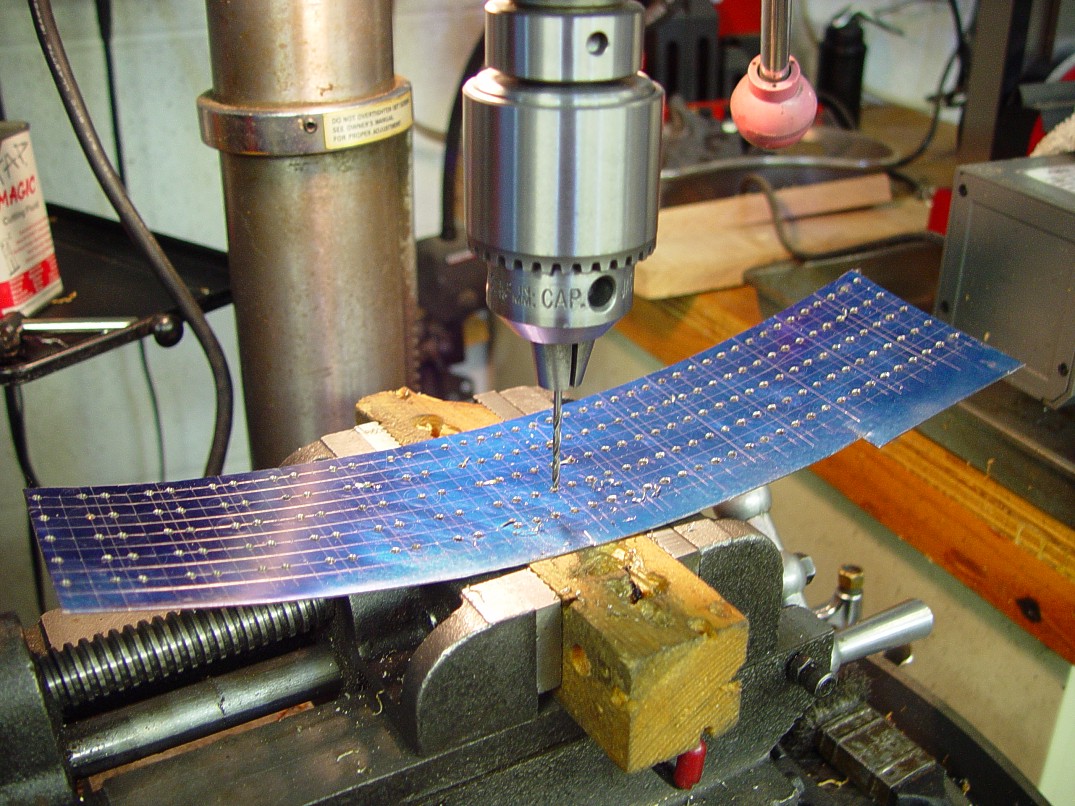

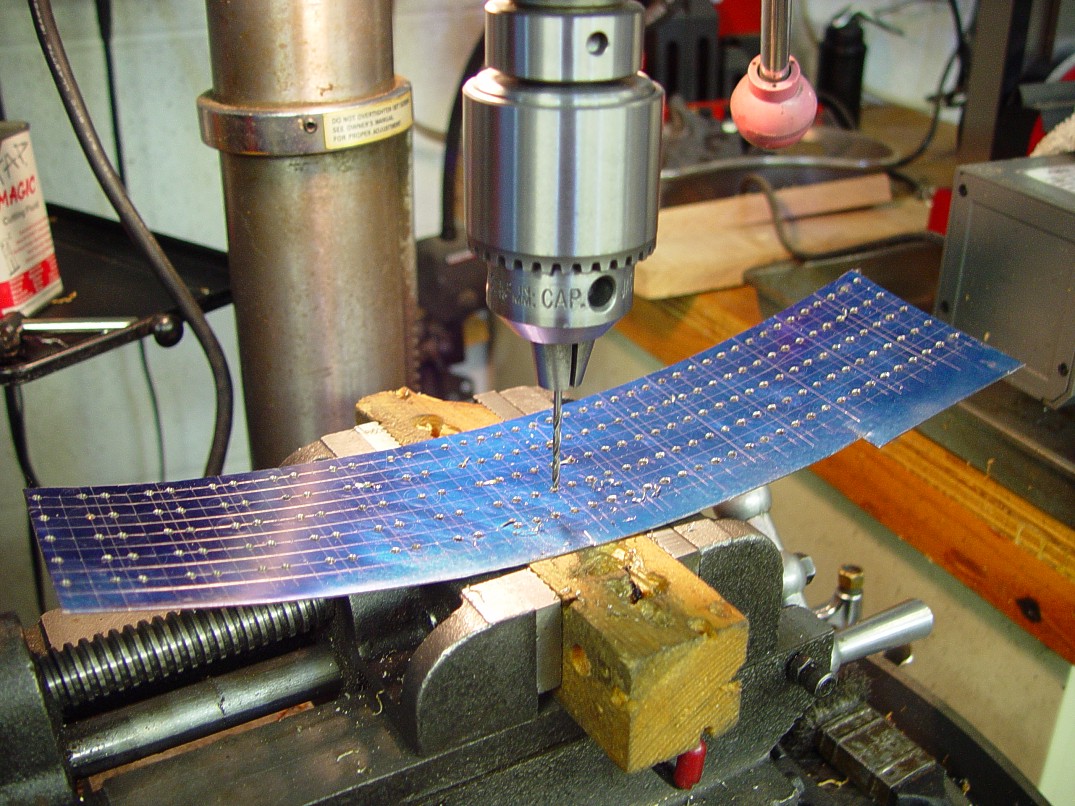

- Photography: If you are like me, you take every

single photograph of your knives, archive them, arrange them,

present them to the public for inspection and record. This also

includes shop photos, process photos, and even photos to record

arrangements of tooling so I know how to repeat a particularly

difficult setup in the machinery.

- Drawing, Painting: all good projects start with

drawings; drawings compose the subtle nuances of blade design,

fittings arrangement and are the basis for all stands, cases, and

displays. They are also the basis of all embellishment, engraving,

detailing, carving, etching, and designing. Painting is done in my

trade with micro-brushes and leather dye, in gentle layers of

toning, density, color, and saturation for a special appearance on

sheaths, stands, or cases.

- Toolmaking and tool steels are obvious players

in the knifemaker's toolkit, and he needs them not only to make his

blades, but also to cut them, mill them, drill them, and shape them.

A machinist is a major job requirement of the successful knifemaker.

- Woodworking is a major player not only in knife

handle construction, but also in blocks, stands, cases, and

displays. Understanding how wood works, moves, shapes, and finishes

is critical because rarely is one single wood type used in these

projects; I remember one of them I made that had ten different

species of wood in the finished product.

- Leatherworking is an obvious skill set that

makers like myself who make their own sheaths must excel in. This is

not a decorative belt or handbag project; these are heavy duty

holders for razor keen implements that must protect the wearer with

logical and sturdy design, hardened construction, and striking

beauty. In addition to cow hide, the successful leatherworker in

sheaths must understand exotic skins and how to use them. Carving,

tooling, and hand-dying are also necessary skills.

- Manmade materials craftsmanship and

applications are critical to understand in the knifemaking world.

Loosely called plastics, these materials comprise modern polymers,

phenolics, polyesters, and poly-epoxide thermosets as well as

pressure stabilized hardwoods and organic materials. Handles can be

constructed of the most durable of these materials, and sheaths,

fittings, and accoutrements require their use along with metallic

hardware and an understanding of how the two combine and interact in

the entire assembly. Textile applications of nylon, polyester,

polypropylene, and even Teflon are required in military combat gear.

- Lapidary is a rare application, but in my

distinct tradecraft, it is a major player in the completion of my projects.

Lapidary requires a very wide skill set, as rock, stone, and minerals

are some of the most tenacious and labor intensive materials to work

and finish.

- Chemistry is not often considered part of

knifemaking, but it plays a heavy role in the versatile knife

studio. Etching, plating, soldering, anodizing, passivizing, bluing,

and chemical staining are essential processes to understand and

effectively apply in modern knifemaking.

- Sculpture is seldom considered as knifemaking,

but this is really the essence of knives, as they are three

dimensional objects. The knife doesn't just need to look good

sitting there, it must be held, be comfortable, even inviting to the

human hand, while being beautiful and unique. All this while

performing the sometimes forceful task of cutting, ripping, and

carving. Add to this the advanced knife artist creates sculptural

stands, fittings, and displays and you might find him sculpting in

clay, wax, or other media and hand-casting the display sculpture in

bronze. I do! I know of no other objects made by man that fit this

profile.

Wow! Who knew there was so much to being a knifemaker? Add to this

the essential skills that go on behind the knife; machine tool

construction and repair, electrical repair, maintenance, and invention,

HVAC, safety process, jig and fixture component construction, and all of

the typical things it takes to run a business, finance, and accounting, and the skill set can be

significant!

This is why I love this job. Always something new, always a

challenge, and always a thankful reward for the most important thing

applied to any work of fine craft or art: labor of the artist's

hands guided by the brain God was kind enough to supply.

Back to topics

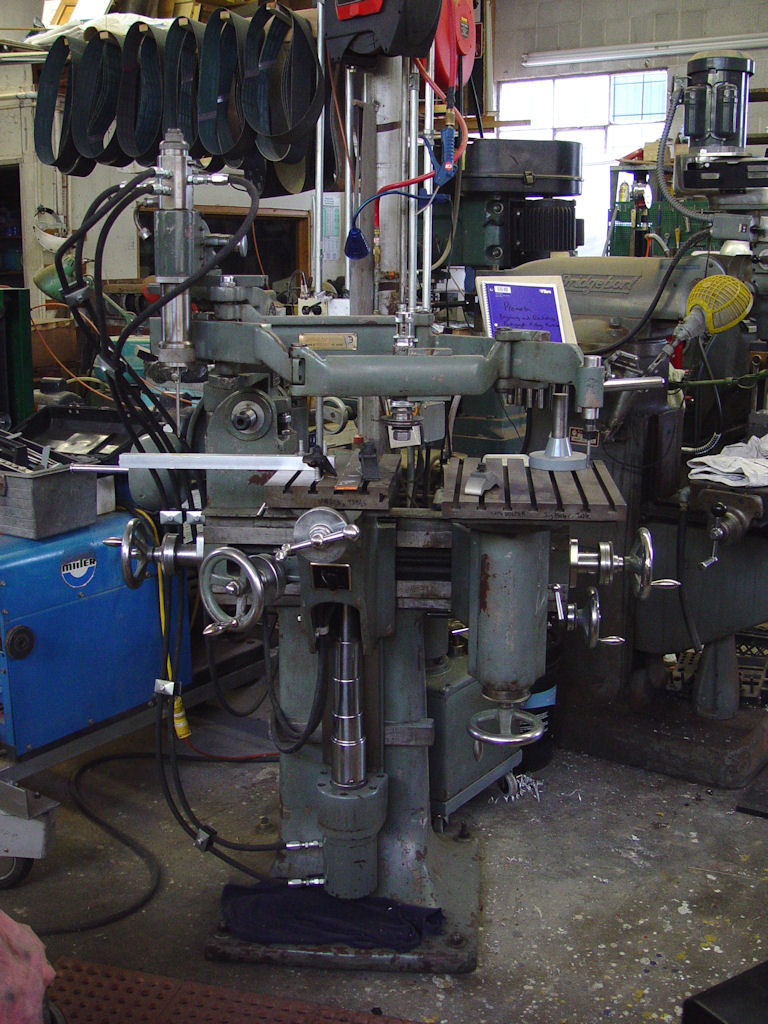

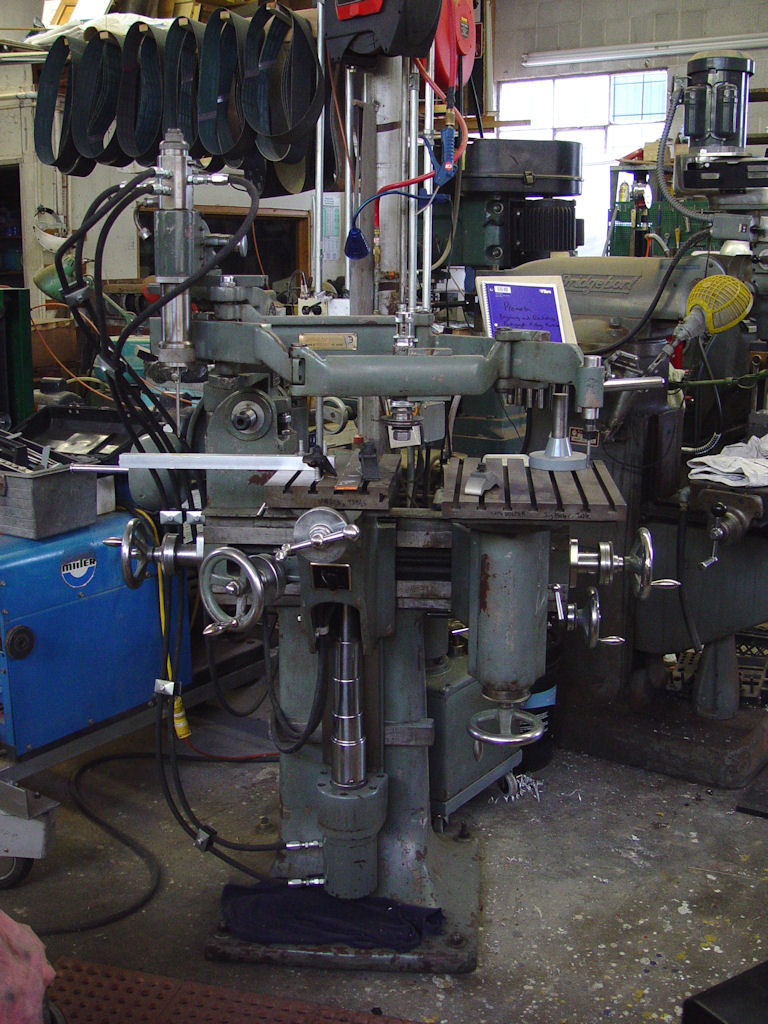

A simple, hand-operated three dimensional engraving and die-sinking milling machine

It is the material that determines the maker's methods and techniques; the most refined materials

require the most specific and controlled methods. Lesser materials

can be handled with casual attention.

What is the difference between a blade smith and a stock removal

knife maker?

The fact that a knifemaker is hammering out red hot metal on an anvil indicates he is using an inferior, low alloy tool steel.

The highest quality blades with the highest performance cannot be hand-forged.

People who buy the idea that a hammered blade is somehow superior to high alloy tool steels are buying the

false image, not the reality.

The two names below describe how the knife maker

makes the knife blade. Though I've hand-forged knife blades in the

past, I currently make by the stock removal (hand-guided machining) method because it allows

me a higher quality, better performing, and greater range of high alloy tool steels.

- The blade smith (or Bladesmith) uses

time-honored techniques of hammer and anvil, and forges a blade

using heat in an open-air forge and process. In this day, he may use power hammers, gas forges, and

modern methods and techniques, but his blades are hammered out of

stock, or heat-forged and welded from various steels. He is not

usually limited to size and shape of his blades, but is limited in

the types of steel he uses. He can only use low alloy

steels and plain carbon steels. High alloy tool steels, martensitic stainless steels, and steels that have high critical temperatures are not

hand-forged, because they can not be exposed to free oxygen

during temperatures at which they can be forged or decarburization

will occur, drastically effecting the steel make-up, internal

stresses, and thus performance. Also, open air forging furnaces are not

capable of maintaining the extremely high temperatures at which

forging of these high alloy steels could occur. Most of the high

alloy tool steels can not be hand-forged, so you will not see them

offered by blade smiths. What you will see are plain carbon

steels like 1025, 1095, and 5160. You'll occasionally see steels

like D2, but if this steel is hand-forged in open air, significant

decarburization will have occurred, severely affecting performance.

In reality, hand-forged D2 is ruined steel. You may see some

stainless steels hand-forged, and this is possible on the lower

alloy types, but performance of these alloys are considerably

limited, making one wonder why the are hand-forged in the first

place. The

low alloy carbon steels have severe

limitations of wear resistance, corrosion resistance, and tensile

strength, but because they are easily forged, forgiving of

error, and cheap, many blade smiths use

them. The main reason that these lower alloy types are

hand-forged is because of a certain look, the look of pattern-welded

damascus, a temper line (hamon line) and appearance only. These

knife blades are created this way because it can be done in a fairly

inexpensive method (no high temperature furnaces, cryogenic process

equipment, or high accuracy tempering ovens are required), and the

visual appeal only is the desired effect. This is the only reason

(visual appeal) that I have and do use this technique and material

for some blades, at the significant cost of lower performance. More

about the failings and limitations of

damascus steels here.

- The stock removal knife maker makes

blades by cutting, shaping, grinding, drilling, machining, and milling stock

steels, followed by heat treating (hardening and tempering) in

controlled-atmosphere furnaces. This is followed by finishing steps.

Generally, he does not hammer forge his blades, but some hand-forging may occur

of fittings and accessories.

The advantage of stock removal is tremendous. High alloy, exotic, and

refined modern

tool steels can be used to make his blades, and these are some of

the finest alloys and metals available in the world today. Heat

treating is done in an oxygen-free or oxygen-reduced atmosphere in

the high temperature accurately controlled environment necessary to heat

treat these steels. The maker can and should use cryogenic

process and equipment to handle these steels, and follow heat

treatment and cryogenic quenching and aging with deep cryogenic

thermal cycling between tempers. Tempering is specifically

controlled in a high-accuracy oven designed for a laboratory

environment. The stock removal knife maker may be limited by

the size and shape of the stock he uses, but nowadays, this does not

have to hinder his creativity. For example, I use a high tech GTAW

welder to create the pieces I need out of very large or wide stock

when necessary, and the technology of the welder, the alloys, and

the heat treating process yields an isotropic, uniform blade of

monolithic high alloy tool steel. Most of my military, professional,

counterterrorism, and collecting clients request these fine steels, because they are

far superior to plain carbon steels in wear resistance, tensile

strength, and corrosion resistance. They are always, always

superior in performance to damascus pattern welded steels which are

created only for appearance. They are, simply put, the best

steels made. More

at this

bookmark on the Blades page.

- Which is preferred? The

techniques and materials are different, and the differences are

significant due to the different steels available for use, and

his control and utilization of the process, based on his experience. Each knife maker must prove his qualifications and

ability with each individual knife depending on components used and

the six distinctions I

listed in the previous topic. Each type of knife making has

its following, its purists, its enthusiasts and its opponents.

I have good friends in both camps, each has a respect for each

other's abilities and skills. Often, each type of maker may cross

over in techniques of blade creation. No matter how the blade is

created, it's important that the knife maker make his own blades,

that they are not farmed out or bought from suppliers or as kits.

Otherwise, he is not a knife maker, but a knife assembler.

- Definitions: It is interesting to note that the

definition of forging is to form by heating and hammering. It

is also defined by shaping metal by mechanical or hydraulic press.

Another definition is to form, shape, or produce in any way. So

when a factory claims that its blades are forged, it may simply mean

that they are stamped out on a die press, which is, technically,

not a lie. Shaping metal by mechanical means could also define

drilling a hole in a piece of metal, so that, too, could be called

forging. Please think about this when you read advertising copy or

vague descriptions of process. This is in every standard

dictionary.

- Differences: No matter the method of the initial creation of

the blade, the blade must be ground, drilled, machined, and finished

in high quality works. Also, bolsters, guards, handles and

sheaths must be constructed, and embellishment in finer pieces must

happen. After blade construction, both the blade smith and the stock removal knife maker have

more in common than in difference.

Back to topics

When thinking about modern tools and technology in knifemaking, there is a natural progression from hand-forging low alloy carbon steels to machining high tech

high alloy steels. The technology then focuses away from the handwork and onto the

machine work. Because machines themselves are technological wonders, and new devices and

operational methods are being developed all the time, the machine becomes such a central part of the work that, at some point, it overcomes the product!

This is true in many fields, and knifemaking is no exception. Take,

for instance the belt grinder. It's a very simple machine, a motor

driving a wheel that drives an abrasive belt around other wheels. The

nuance of the machine is not in the wheel arrangement or accessories,

it's in the hand of the guy that holds the blade against the abrasive.

He controls what is happening via his bare hands, thus, the

machine enables speedy work of hand-grinding. Like all human endeavors,

the idea pops up to make the entire affair, well, easier. After all,

hand-grinding is hard work, and it doesn't always come out right. So the

knifemaker may try jigs and rigs, and devices and contrivances designed

to make the job of hand grinding easier, more predictable, and faster.

In the decades I've been making, I've seen every type of device made to

do this one simple step in hand-grinding, and as yet, not a one of them

is worth the time it takes to bolt them on the tool rest.

The reason is simple. The human hand, when trained and skilled, can

sense, adjust, and correct an incredible amount of geometries, angles,

directions, pressures, an movements, all instantly. A jig simply holds a

blade and allows it to be moved side to side. The jig cannot create a

radiused hollow grind, cannot create varying angles and thicknesses

along a curved blade length, and cannot accommodate a recurved hollow

grind that is narrower than the belt. Worse still, a jig cannot create

subtle differences in pressure, direction, and flow that allows ten

steps of increased grit size for proper and accurate mirror polishing.

This is why very few knives are mirror polished at all, and of those,

fewer still maintain accurate geometry that is not destroyed by an

overzealous buffing wheel.

Learning this stuff is hard. The guys that I teach in my studio can

tell you just how difficult it is, and also how valuable this skill and

its results are to a patron and client. Rather than study and train for

years to achieve this result, craftsmen continually search for an easier

way. The truth is, if it were easy, everybody would be doing it, and

then it would have little value. But the search continues in an effort to shorten,

quicken, and improve the work, and because we are enamored with the

machine, we try to build and use more complex machinery to do this work.

The CNC machining center is a good example of this. The machine uses

the logical commands programmed into a computer to establish a set of

functions for the machine to execute in order, and the human hand has

little to no contact in the operation. Machined parts can be cut,

drilled, milled, ground, shaped, radiused, slotted, and created almost

wholly under the changing turret of cutters. The advantage of this is

tremendous speed and uniformity of operations, so the machine is

well-suited to production. Naturally, knifemakers are all about

production, so one of these sounds like a great solution.

If this were true, we artists and craftsmen would be out of business!

But we are not, and there are some simple reasons that the answer is not

always in the machine. It comes back to that human touch. The machine

cannot apply this, no machine can. It is the union of the machine with

that variable, adjustable sensitivity that allows microscopic tweaks of

movement and pressure to create flowing, finished, and artful forms,

forms that simply don't look like they were cut out by a machine. And

that is really all you get with a CNC: forms cut out by a machine. The

total piece then becomes an assembly of parts that all look like they

are cut out by a machine, and because machines mass-produce, the value

is low.

There is a type of consumer, however, that is more enamored with the

process than the creation. He would rather describe to his friends the

complexities of the computer-driven process and the

big machining center that milled the knife than the knife itself. After all,

it's flatly ground, squarely jimped, with all parallel surfaces, and a

flat and lifeless surface, which wouldn't even be called a "finish."

Some are step-milled, in a machine attempt to build a hollow grind that

ends up looking more like a set of stair steps than a blade grind. Perhaps

the blade is sprayed with paint and baked. Perhaps it has bolted-on

handle scales with three simple rivets or screws down the centerline.

And it may not even have a functional sheath. But the machine that made

it... well, you just won't believe it; it's a magnificent work of

technology!

I don't use the newest and fastest ultra-modern computer driven

technology in my studio. This tech actually would limit what I do,

because nothing can replicate the creations of the human hand, eye, and

touch. If it did, I would be out of business! Since this shows not the

slightest hint of happening, I can only surmise that the role of the

human hand has not been supplanted.

In recent years, great advances have been made in machinery,

particularly with computer interfaces and control, and we all

certainly hope that they can help us create a wider range of specialized

items. But for now, the operations of a machine limit what can be done,

they don't extend it, amplify it, or improve what can be done by skilled

hands. And a knife made by a machine is less in value, appearance, and

desire, than what is made by hand.

Back to topics

More

More about this Israeli Defense Force YAMAM Unit "Ari B'Lilah" counterterrorism knife

Seems simple, right? It's a knifemaker who does this as a profession,

as his main, full-time source of income, officially, legally, and in a

business environment, right?

I've read several online sources, discussions, and articles about "Professional" Knifemakers, and there seems to be a lot of confusion and misplaced

descriptions about what constitutes a professional knifemaker. I'll get into the reason that this is a confused title and I hope that for the sake of the

knife client, owner, patron, or customer that this section will help clear that up.

In this context, the word professional typically means that

a professional knifemaker does this for a living, as a profession, and this is his main

and central focus, way of earning a living, and is registered legally

and officially by

local, state, and through the federal IRS and governmental agencies as an

occupation. A professional, then is a full time, occupational

knifemaker.

A part-time knifemaker is not a professional knifemaker, nor is a

hobbyist, amateur, or person who simply likes to make knives. There are

all sorts of uses for the word professional, such as acting

like a professional, having professional standards, or being in a

profession. Perhaps this has confused the identity of the professional

knifemaker, and frankly, everyone, from amateur hobbyist to part-time

knifemaker wants to call himself a professional, because doing so paints his

practices and skill as, well, professional! This is done for one reason, to

portray

a picture of one as better than they are, because it's assumed that a

professional occupational knifemaker will have a greater understanding,

knowledge, and skill as a craftsman, tradesman, artist, and business

professional. But calling yourself a professional for these reasons is

frankly disingenuous, inauthentic, and lacks integrity.

How to tell:

The person who claims to be a professional knifemaker would (by law

in the United States) have these essential and critical items and

traits:

- A Federal EIN (Employer Identification Number)

is absolutely required nowadays by every professional

business; there simply is no way around this. If one is a hobbyist,

part-time knifemaker, or amateur, the determinant factor is often

this very number. This number means that the professional business

files a Schedule C IRS form (Profit or Loss in a Business) and is

federally registered, and regulated, indexed, and identified by the

United States government.

- A business license

is typically required by the state in

which the professional is located. This is critical to define,

regulate, tax, and inspect any business, in any state. It defines

the business and typically registers its name and location. It's also used to

access tax information, filing, and other business essentials

defined by the individual state. In our state, it requires us to

collect state taxes on any in-state sales.

- A business registration, accessible by local

authorities and jurisdictions. This may vary somewhat, but usually

any person doing any kind of business is required this. Cities,

towns, and counties typically require this for any professional

occupation, and it's fairly easy to look this up in the local

business directories of those entities.

- A certified, inspected, and unique business address

and storefront is usually required by professional

businesses. Certainly, when a part-time maker is working in his

garage, this is not the case, but a part-time maker working in his

garage is not a professional, either. While the part-time maker may

be required by zoning and local laws to have a state business

license or local business registration, there is a level of

commitment that may be in question when a client considers the

environment where a knife is made. Without a professional business

address and storefront, the official entities (Local, State,

Federal) can and do question whether this is a hobby, an interest,

or a profession. Some professionals work from home, but rarely does

a home contain a professionally outfitted, full time

knifemaking shop or studio.

- Full time employment as the main source of

income is the determinant factor that most official entities use to

certify, regulate, and classify a professional. Since there is no

standard of education or certification for what constitutes a

professional knifemaker, the full time employment distinction is

essential for official and legal identification. While it may be a

difficult issue for the client to determine, it's clear to federal,

state, and local authorities where the knifemaker's money comes

from, how much of it he makes, spends, and invests in knifemaking,

and this is what makes these legal authorities license, accept, and

classify the business. It is a business, and sooner or later, the

professional business aspect will be clarified, after all, it's the

law.

Other related items not necessarily required but important to the

knife client, patron, or customer that accompany a professional business

are:

- Visitation by the client. If people

are not allowed to visit the studio or shop because the location is

residential (typical in part-time knifemaking), this also suggests

the non-professional, non-occupational method of knifemaking.

Visitation may be tightly controlled or restricted (mine is,

conforming to local laws), at least the client knows exactly where

(and how) his knife or knives are made.

- A business and professional bank account is

necessary so that business related transactions are conducted

separate from personal accounts. Bank transfers, credit cards,

payment methods and other business transactions are conducted in the

scope of dedicated professional means. This goes hand-in-hand with

the Federal registration and business codes require above, and

reassures the client that the professional business is on good

foundation with an established financial institution.

- A functional, detailed website is absolutely critical in today's

professional business world. I've stated before that most

professionals will have this curriculum vitae available, and today's

method is through the internet. Curriculum Vitae means "a brief account

of a person's education, qualifications, and previous experience,

typically sent with a job application." You may not think this

applies, but consider that if you are going to buy a knife, you will

be employing the individual knifemaker, and therefore, your contract

together is an agreement that the knifemaker works for you. Every

knife made and sold is a job application. If I, as a singular

professional knifemaker can provide hundreds of pages of detailed,

researched text, tens of thousands of photos of made and sold

knives, hundreds of testimonials of satisfied customers on this very

website, there is no reason that any other knifemaker who calls

himself a professional can not and will not offer this insight into

his professional business. Maybe other professional makers aren't

able to offer this type of illustration, but let's cut this down to

10% of what I do. With only 10% of what you see here, that would

mean a professional knifemaker's website will have at least 50 pages

of related data and about 700 unique, original photographs. Again,

this is not a requirement, just an indicator of the professional

standing of the knifemaker being considered by the client.

There is a lot more to this, and I'll go into it in great detail in

my book, but guys will take the name "professional" and interpret it to

mean something else that justifies the title for themselves, and this

can be quite humorous. I've seen discussions that claim that if the

maker can grind a bevel (technically called a grind or hollow grind),

fit a handle, dovetail a bolster, and tightly fit a guard, he can call

himself a professional. I've also seen it written that if he buys 50

sheets of sandpaper at a time, he's a professional. I laugh at the claim

that if a knifemaker has a bathroom in his shop, he's a professional. I

hope these are seen as "trying to make knives in a professional way,"

and not the statement that these simple comparisons are what constitutes

a full time professional occupational knifemaker.

A professional knifemaker is one whose main

or sole source of income is making knives and their related

accessories. He is registered and accounted for by Federal, State, and

Local authorities, has a professional business storefront, and an easily

accessible reference to his works, method, and business practices for

whatever time he's been making. A higher level professional is sought

out for his knowledge and experience in the tradecraft by businesses,

persons, organizations, and official entities to advise in an expert

capacity, as a Professional Knife

Consultant.

Patience, willingness to learn, and dedication

alone do not make a professional.

Full time employment, scope and detail of applied knowledge,

specific legal requirements, and clear record of achievement and

experience make the professional knifemaker.

Conduct is the determinant factor.

Nature has made occupation a necessity to us; society makes it a duty; habit may make it a pleasure.

--Edward Capell

1713-1781

More about what constitutes a professional and the standards associated with this declaration on my Business of Knifemaking page

at this bookmark.

Back to topics

More

More about the "Antheia" Chef's Set

Modern knife making has progressed dramatically in the decades I've been involved. Steels

have improved, as have abrasives, computers, adhesives, and communication which allows you

to see the many knives available and read plenty of information on this topic by guys like

me who do this for a living. This very site is a service that I had not envisioned as useful

or available when I started seriously making in the early '80s. It is

now not only essential for

my business, but also my sole business attribute. I no longer take dangerous and

arduous trips to shows and exhibitions; I create my own knife show on this very website. Communications and

web technology allows me access to new materials, design ideas, process information, and suppliers.

It is the new medium of knife making. Where else can over two million people see my knives in the course of a

month? It's a fascinating and exciting field, and I'm proud to be a part!

Back to topics